A Thing for the Mind

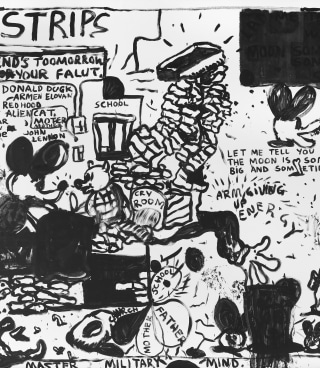

Six decades after Philip Guston (1913 – 1980) first shocked the art world, the sweeping ambition of his vision continues to reshape the realm of the possible for artists who have followed in his wake. His paintings blend a precise vocabulary of concerns then without precedent in American painting: mundane domestic objects, body parts and cityscapes within abstract fields of paint. As humorous and personal as they are politically incisive, his paintings draw a vivid picture of Guston’s own muddled dreamscape of fears and anxieties as well as of society’s worst impulses.

Taking one of Guston’s most celebrated paintings – his 1978 masterpiece Story – as the heart of the exhibition, A Thing for the Mind presents work by twelve contemporary artists whose work continues to be influenced by Guston’s ideas: Louise Bonnet, George Condo, Carroll Dunham, Armen Eloyan, Maria Lassnig,Chris Martin, Eddie Martinez, Woody De Othello, Daisy Parris, Walter Price, George Rouy, and Antonia Showering. ‘A painting should be a thing for the mind,’ Guston declared of his philosophy, paraphrasing Leonardo da Vinci.

Artists George Condo (b. 1957) and Louise Bonnet (b. 1970) explore the grotesque in the human experience, balancing satire with rich chiaroscuro evocative of Old Masters. Like Guston, both are interested in the lessons of cartoons as social satire. Bonnet’s lustrous oil works contrast delicate lines with exaggerated body parts, parodying our disgust with the uncontrollable, unmanageable human body and its base desires. Condo’s charcoal drawing owes a debt to Cubism; his bulb-eyed figures are layered in a network of fractured geometries, like instruments in a classical orchestra.

In the same way Guston once populated his paintings with industrial landscapes, Eddie Martinez (b. 1977) and Carroll Dunham’s (b. 1949) paintings draw on urban sights. Absence and brightness collide with fireball bursts of speed in Eddie Martinez’s layered paintings, which blast abstract forms over white walls of paint. In contrast, Dunham’s pink-hued painting evokes the playful surrealism of Guston’s Story, which juxtaposes a cigarette-smoking hand with disembodied objects such as a snail and an eyeball. References to vision and mundane contemporary sights —such as the cigarette and the grey-suited man —give us the disorienting sense of peering into someone else’s dream.

Other artists speak to Guston’s desire to turn his inner world outwards through a precise anatomical language. The late artist Maria Lassnig’s (1919 – 2014) expressive oil paintings took her own figure as a distorted biomorphic form, addressing the fragility of the body and the passing of time. Dreamlike haze meets the neon electric in George Rouy’s (b. 1994) sensual portraits, where physical desire is painted as a crackling field of colour over lumpen, skewed bodies. Meanwhile, Antonia Showering’s (b. 1991) ethereal ochre pools describe intimate relationships as Rorschach blots in which layers of pentimento unfold into abstract memories dotted with surreal household objects in a personal symbolism known only to herself.

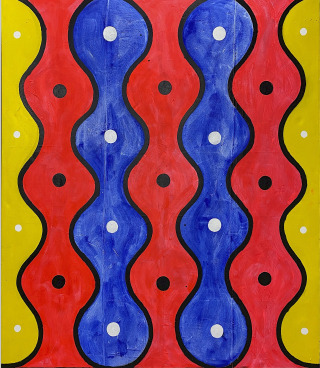

Fractured pools of pigment bleed into Walter Price’s (b. 1989) paintings, in which the artist uses the brushstroke as a tool to abstract images from the news cycle and everyday life. Burning cars, pieces of furniture and fragments of words are floating objects that reflect the disrupted and often inflammatory feeling of modern life. Similarly, Daisy Parris’s (b. 1993) mossy brushstrokes are covered in poetic and political text fragments, underscoring the artist’s belief in a raw core psyche of shared human emotion. Both steeped in downtown culture and graffiti art, Chris Martin's large-scale paintings combine high and low culture in dizzying, glitter-covered shades of vibrant oil paint, while Armen Eloyan’s work depicts absurd narratives in cartoonish abstraction, adroitly balancing dark humour with a searing existential vision.

In an echo of Philip Guston’s vocabulary, Woody De Othello (b. 1991) inflates household objects to dizzying size. Often adorned with human features like ears or mouths, these playful ceramic sculptures draw from the Yoruba concept that objects can be imbued with a protective spirituality. They offer the viewer a different way of reflecting on our history and experiences: through the personification of the objects that constantly surround us.

Many of these works encapsulate a tension between the vibrant inner landscape and the disquieting outer society, interpreted through the lens of commonplace objects that comprise our everyday environments. A Thing for the Mind invites viewers to reconsider the domestic spaces and images around us: from the inside out, charged with our own personalities, emotions and desires.

Image: Philip Guston, Story, 1978. © The Estate of Philip Guston