The Bitter with the Sweet

Tucked away in a 400-year-old barn on her family's farm in Suffolk, England, Sahara Longe created a collection of works that expresses the moodiness and isolation of her environment. For nearly a year, her rural-almost certainly haunted-studio has been fit for the pages of a Gothic novel, with mysterious scratched markings adorning the woodwork and the occasional flickering light inducing a chill. The setting is at odds with the images and themes that initially inspired her to press brush to canvas in this new body of work. Reflecting on the history of the hypersexualisation of women in Western art, Longe first set out to explore the female nude in a way that showed women in full, confident possession of their sexuality. But the spectre of something else-perhaps a pensiveness brought on by her surroundings-persisted.

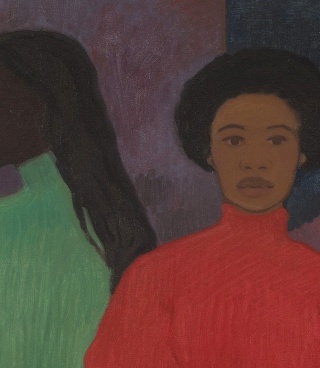

In As We Are (after Otto Friedrich), we see a group of nine women brazenly presenting themselves in a manner that dictates how they want to be seen. The composition is inspired by the painting Wie sie sind (As they are) by Vienna Secession painter Otto Friedrich, which depicts nude women in similar poses. Longe takes possession of the scene by using her own face as a model for each figure and shifts the "they" in Friedrich's title to "we" in her own. Additionally, where the expression of Friedrich's models is coy-averting their eyes or facing away-the women in Longe's painting look directly out of the canvas to confront the viewer with a range of emotions. The scene, which serves as a remediating response to historical conventions of representing women, is further activated by the surprising presence of a shadowy figure. The woman at the right of the group extends an arm to the being, and what could be interpreted as a looming, fearful presence is shown to be welcome in this scene. This spectral figure appears in multiple paintings in the exhibition, including Nude and Bad Dreams (after Ferdinand Hodler), and Longe views its presence as an embodiment of her own mind-a visual representation of self-reflection.

Longe notes that As We Are is a nod to Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, which famously depicts nude women in fearless, commanding poses. It is in these types of layered references that we see how her practice is often in visual dialogue with the past. Having grown up drawing on the walls and the occasional scrap of fish and chips paper with her sisters, Longe originally pursued her interests by studying art history at university. Soon, she realised her talents were better applied to painting than to essay-writing, and she redirected her studies to train in classical portraiture at the Charles H. Cecil Studios private atelier in Florence. Following this period, a visit to her mother's native country of Sierra Leone combined with explorations of Gauguin's colour palette of emerald green, cadmium yellow, and cadmium red, shocked her practice into a new phase. Her training was steeped in Western painting, but her use of graphic colour has imbued her practice with a fresh and captivating edge, contributing a bold and layered perspective to contemporary figurative painting.

She frequently absorbs inspiration from unexpected places, incorporating these eclectic elements into her own visual language. On a recent trip to Norway, Longe visited the National Museum in Oslo and was captivated by the Christian iconography art on display. In one painting depicting Jesus on the cross, she admired the colour palette of a textile in the background and employed it in painting Nude with Checks. She also observed that several paintings contained painted frame-like borders, and returned from the trip with a new interest in exploring the effects of framing in her work. Disappointment is situated within a solid black painted border which reflects the emotionally charged subject matter, but Liar and Good Time / Bad Times sit inside colourful borders of shifting organic shapes, as if the scenes within are being distinguished as dreams or recollections.

Inside of its painted frame, Good Times / Bad Times depicts a border of nineteen tableaus-images showing family, loneliness, passion, friendship, love, and loss. The scenes surround the nude figure of a woman holding the shadowy phantom that appears throughout works in the exhibition. The format of the composition is one sometimes found in medieval Christian icons, which depict key scenes from the life of a saint around the edges of a central image. Here, we understand that the pictured memories belong to the woman and that by embracing the shadow, she accepts herself and all of the good and bad that comes in life.

The show's title, Sugar, offers further insight into this notion of taking the good with the bad. With Longe initially setting out to depict cool, sexually empowered women in her paintings, she thought to call the show "Suga," which she felt was a "sexier" spelling that indicated the word's use as an endearment. As the women in her paintings came into being, however, she found that they expressed more than she had anticipated. Some are bold and self-possessed-yes-but others are sad or nervous or lost in thought. Longe decided to go with a more serious spelling of "sugar" to pull back on the levity and hint at life encompassing a mix of bitter and sweet, bad, and good.

It would seem that the isolated setting of her studio laid the groundwork for this introspective collection of paintings. In creating these works, Longe let the imagery dictate itself, leaning into unforeseen directions and plumbing her own experiences and emotions along the way. There is a vulnerability to the paintings, wherein the artist bares much of herself but also leaves space for viewers to fill in the gaps or project their own interpretations. She is not precious about how the paintings should be understood and uses open-ended symbolism and titles that invite viewers to find their own meanings. We can at least take encouragement from the sweet title of the show that things have a way of working out for the good.

Sahara Longe: Sugar is on view through 15 June 2024.

About Ferren Gipson

Ferren Gipson is an art historian and artist researching modern art and exploring themes of politics, popular culture, and identity. She is the acclaimed author of Women's Work and The Ultimate Art Museum, and as a dynamic storyteller, has contributed to the Financial Times and hosted the Art Matters podcast. Within her textile art practice, Ferren explores themes of spirituality, materiality, and matrilineal ties.