A Room, a Knot: Jorge Eielson and the Mysteries of Humanity’s Bare Necessities

Upon arriving in France in 1948, Eielson became involved with the activities of the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles and found what he would call ‘poetic physics’ in artist Jean Peyrissac´s dynamic artefacts. These responded to the force of gravity and could simultaneously function as sculptures, machines, or architectonic elements, thus agglutinating geometrism, cosmology, and a contemporary understanding of light and space. This interdisciplinary line of reflexion—based on the philosophical, symbolic, and visual implications of scientific methodology, concepts, and technology which were developed during the early stages of the Space Race—would allow Eielson to connect the work of Peyrissac, of Yves Klein and that of Lucio Fontana to his own interests. After moving to Rome in 1951, Eielson’s exhibition of mobiles in the Galleria dell’Obelisco, in 1953, responded to that same European context. That year he would meet members of the Gruppo Origine, such as Giuseppe Capogrossi, Alberto Burri, and writer and artist Emilio Villa; the encounter with the latter would reignite Eielson’s studies of Pre-Columbian traditions he carried out in Perú under the mentorship of Emilio Adolfo Westphalen.

Little is known about Eielson’s visual work from that year up to 1958. The poetry collection A Room in Rome written throughout the 1950s, could be considered a chronicle of a period in which Eielson gave form to his interdisciplinary poetics. His writing articulates principles from informal visual abstraction, combinatory concrete poetry, a possible encounter between ancient sacrality and modernist artistic gestures, and a spiritual and celebratory attitude towards life and existence which were to be understood as rhythmic manifestations of the dynamics of the cosmos. Eielson’s room in the ancient Pagan and Christian city resembles a spiritual dwelling that reconciles the modernist modulor, the hotel room, and a sort of a secular urban monastic cell. Life within such a room’s four walls is presented as a process of reduction to the bare necessities: a handful of garments, a few pieces of furniture and a series of daily repeated ritual-like actions accompanying days and seasons. The collection closes with a text, ‘a sculpture made of words’, aimed at making evident that any poem’s purpose is to exist as a communicative gesture of emotional intelligence rather than being a producer of meaning.[1] In his visual work, the process of reduction would be mirrored by images of minimalist abstraction, the presence of concrete objects would replace meaning, and traces of gestures would be granted unexpected transcendence.

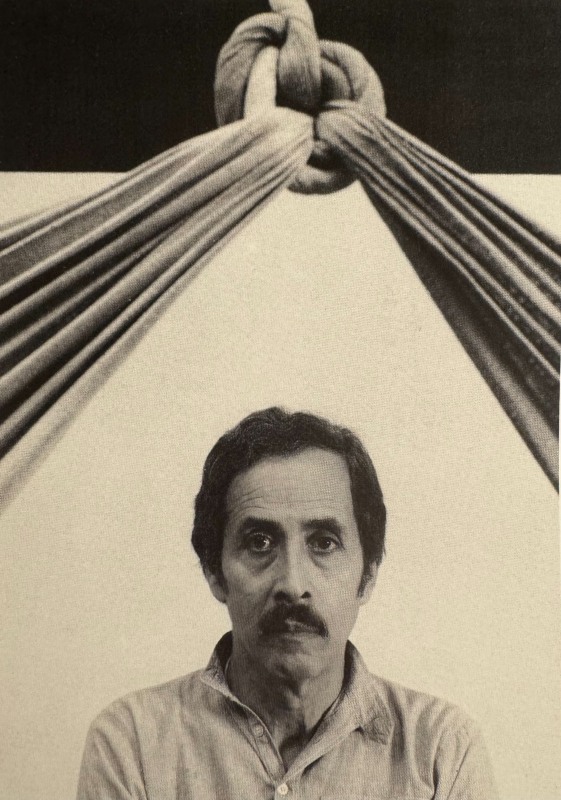

In 1959, Eielson began the production of a series of matteric canvases, followed by a series of manipulated garments (shirts, jeans and dresses), and eventually, in 1964, he would produce his widely known series of knots. The matteric images of his Infinite Landscape of the Peruvian Coast establish dialogues with Yves Klein’s ‘nouveau réaliste’Planetary Reliefs, with Antoni Tàpies’s informal ‘walls’ and with Alberto Burri’s Combustions and perforation of non-pictorial matter. These three artists resort to the irrational when not reaching—as the first two did—for the magic or mysterious of non-European philosophical and visual traditions. Eielson’s landscapes are references to orographic surfaces seen from outer space, as are Klein’s, but his pinpoint South America’s geomorphology specifically. Eielson’s landscapes, like Tàpies’s ‘artistic organisations’ of matter, aim at triggering the perception of realities in process of becoming with a participant gaze. The matter emerging from Eielson’s canvases consisted of layers of sand brought from the actual coastal deserts at the shores of the Pacific Ocean. On the other hand, Eielson’s ripped and burned Shirts address what he called the truthfulness and unavoidable presence of essential and humble elements needed for human existence. They also reflected Burri’s energetic routing of the properties of material reality and of humanity’s inner forces that lack rational explanation.

By 1965, Eielson’s knots—called Quipus by the artist in homage to the ancient Andean mnemonic system made of knotted coloured cords—are part of an archipelago of artworks produced during the 1950s and 1960s by several artists—such as Fontana, Burri, Salvatore Scarpitta, Piero Manzoni, and Enrico Castellani. All these items were connected at that time by a common interest in avoiding figurative illusionism and focusing instead on the treatment of light, space, and visual patterns brought to the surface of the traditional canvas through the exhibition of matter, and in many cases, textile matter. Working during the postwar period, each one of these artists was also influenced by the new political, economic, and cultural cosmopolitanism which had emerged in the wake of American reconstruction policies in Italy.

The work of Fontana aims at addressing space as a previously unconceived dimension; the viewer is confronted with ruptured matter, with surfaces and mass that fall beyond the realm of sculpture or painting. Castellani’s work, on the other hand, involves the construction of regular geometric structures on the materiality of the canvas through the production of patterns of luminosity and haptic depth. The textile material would be perceived as a new presence lingering between the viewer and the support. In both cases, viewers are not offered meaning but are instead invited to be witnesses to the existence of what is in front of them. Eielson’s Quipus consist of twisted and knotted sheets of fabric geometrically stretched over canvases tightened on wooden frames. What had previously been garments in earlier works were now distilled to fabric, to the act of weaving, and ultimately, to the bare knot.

However, Eielson’s are not ordinary knots. By associating them with the notion of the quipu, Eielson links them to millenarian cultural traditions, spirituality, and epistemes alien to Europe. Many quipus were found among other garments and objects as integral parts of funerary bundles at ancient burial sites along the Peruvian coast, where they are commonly unearthed by the wind or human activity.

On the stretched canvas, Eielson’s Quipus are presented as foundational construction units, similar to the repeated, combined, and permutated strokes of Giuseppe Capogrossi in which Eielson saw ‘an accumulation of digits or letters in a nascent state... an art that proclaims, day after day, the solemnity and magic of human and natural events, the inevitable power and freshness of the creative forces of our species’.[2] In the work of both Eielson and Capogrossi, therefore, the artist and intellectual Emilio Villa identified the latent presence of a primordial gesture in the modernist stroking and knotting. The quipus brought to existence by Eielson are not magical: the knot is an ancient functional topological object and hence, an inevitable, everyday presence. Nevertheless, its genealogy and transformative potential are a mystery to us, as mysterious as the trace of the stroke or the action of fire. All of them lie at the core of human creativity, and, because of their unreachability, they are touched by the sacred. In 1956, a few years before producing his first quipu, when pondering the organised order of reality offered to the viewer by Mondrian’s grid, Eielson posed a telling question: ‘And who will be able to decide with precision whether the supreme light of human conscience and intelligence does not exert on our ultra-modern sensibility the same supernatural suggestion that the darkness and mystery of existence exercised on the peoples of antiquity or on the primitive societies of the present?’.[3] From the functional textile production found in the ancient burial grounds along the Peruvian coast, Eielson rescues the materiality of a reticular, but also fluid way of understanding the universe and of celebrating humanity’s creative existence.

About Luis Rebaza-Soraluz

Luis Rebaza-Soraluz is the author of The Construction of a Contemporary Peruvian Artist: Poetics and National Identity in the Works of Arguedas, Westphalen, Sologuren, Eielson,

Salazar Bondy, Szyszlo and Varela (2000), and On Ultramodernities and Their Contemporaries (2017). He has edited Arte poética (2005) — an interdisciplinary anthology of Jorge Eielson’s work, as well as Commented Ceremony (2010) – Eielson’s essays on art, aesthetics, and culture – and Commented Ceremony: other Pertinent Texts (2013) – the critical production on Eielson’s visual work from 1948 to 2005. He is currently a Reader in Latin American Visual Arts and teaches cultural analysis at King's College London.

[1] ‘Escultura de palabras para una plaza de Roma’ (Sculpture Made of Words for a Roman Square). In Jorge Eduardo Eielson, Poesía escrita (Lima: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, 1976), 216-218.

[2] Jorge Eduardo Eielson, ‘Capogrossi, pintor de las mutaciones’ (Capogrossi, Painter of Mutations) (El Comercio [September 1955]).

[3] Jorge Eduardo Eielson, ‘Homenaje a Piet Mondrian’ (Homage to Piet Mondrian) (El Dominical, Sunday Supplement of El Comercio [February 1956]).