Dubuffet: Late paintings

Timothy Taylor is honoured to present an exhibition of Jean Dubuffet’s late works. The exhibition maintains the gallery’s interest in late-period European Modernism, and expands upon its programme that includes Antoni Tàpies, Hans Hartung, Serge Poliakoff and Simon Hantaï.

The exhibition brings together key examples of painting, sculpture and works on paper, including L’Hourloupe cycle works of the late 1960s, significant examples from the Théâtres de mémoire of the 1970s, as well as remarkable works from the Psycho-sites, Mires and Non-Lieux series of the 1980s.

Well-known for founding Art Brut – art produced outside of the confines of academic (accepted) art – Dubuffet championed, throughout his life, the need to continually question the established conditions of art, culture and society. He consistently challenged the canon and convention, and for this reason, Dubuffet’s work and ideas remain compelling and relevant. As he states:

… freedom from conditioning implies an antisocial temperament – a position that sociologists classify as alienated. It is precisely this temperament, however, that seems to us to be the very mainspring of all creation and invention – the innovator being in essence someone who is unsatisfied with what others are content with… – Dubuffet, in “Let’s make some room for uncivic behaviour”, 1967

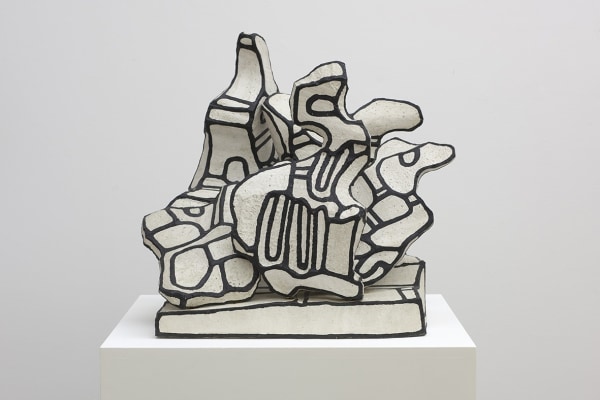

The Hourloupe series is derived from semi-automatic doodles made with ballpoint pen while Dubuffet was talking on the phone, and is the longest series in the artist’s career. The distinct shapes are delimited by black lines, surrounding flat patches of primary red and blue, with white empty spaces. The series would occupy Dubuffet for twelve years and gradually involved the production of art on an industrial scale and incorporating different media and techniques. As the practice moved from that of the traditional painter, to sculpture and architect, these began to include vinyl paint, painted polystyrene and other materials of the ‘common man’. Hourloupe is the title of a small book that Dubuffet wrote in 1962, comprised of ‘absolute jargon’ – a text composed of invented words whose meanings are problematic. The text was decoratively handwritten in white gouache on black paper, and Dubuffet explains the motifs are: “meandering lines with some areas hatched or filled in with uniform areas of colour” and which “produce a disorienting effect particularly as a result of the ambiguity between which spaces should be seen as full and which should be seen as empty…”

Considered as both painting and writing, the series consists of ironic figures and forms in movement, and for Dubuffet was a “festival of the mind” – a representation of the world, far removed from a conformist vision.

The first four series following L’Hourloupe questioned the place of everyman in nature. Figures – alone or in pairs, with no communication between them – are enclosed in halos, and located within vast abstract landscapes (sites) of colour. Dubuffet referred to these works as “landscapes of the brain”, and were the artist’s attempt to represent things as he thought, rather than saw.

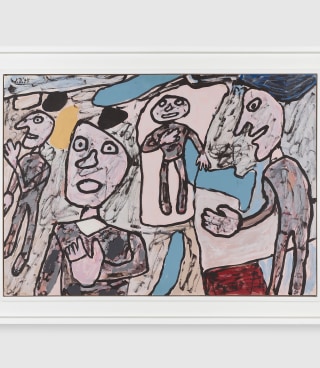

In Théâtres de mémoire, for example – an important series comprising almost 100 works, all large in format – abstract graffiti and figurative forms exist together in a framework of cacophonous space. Amorphous shapes are juxtaposed with clearly realised images and objects co-exist with figures that have no apparent relationship, as in the important example, Garden Party (1976). Dubuffet explains that the figures, “have only an incidental function: they help to polarise the place, to give it voice.” The series began with cut-up fragments of paintings scattered on the floor, where the happy accident became the driving force, as Dubuffet took advantage of random juxtapositions. This strategy is especially analogous to our experience of the world in this moment, where information is accumulated through an often random process that traverses history, culture and geography.

In the subsequent Psycho-sites series, Dubuffet continued his exploration of physical and mental environments of the individual. Here, isolated and interactive figures are suspended within brightly coloured topographies, for example, Site avec 5 personnages (E 175) 13 juin 1981 (1981). As Dubuffet states: “It seems to me that anyone who wants to communicate an idea of what is happening in his or her mind at any time can only do so by way of a cacophony of dissonant elements.”

In Dubuffet’s last two series the artist took a decisive metaphysical turn, as the figures disappear and only the ‘site’ remains. Yet rather than pure abstraction, Dubuffet explains that while “you will no longer find any object or figure in these paintings – nothing that can be named… they are not ‘non-figurative’. Their aim is to represent… the world that surrounds us of which we are a part.”

The entire Mires series was first presented in the French Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1984 to critical acclaim. In these works, Dubuffet’s primary concern was a meditation on the mind as central to observation. The resulting paintings are unrestricted, vigorous compositions, dominated by primary blue and red on grounds of yellow or white. The painting as ‘mental landscape’ was examined further in Dubuffet’s final series, entitled Non-Lieux. According to Dubuffet, the series arose from “the idea that our vision of the world is erroneous.” The works describe psychological non-places, distinguished by fluid intertwining lines and radiant colours, and are comparable to the last works of artists such as Hartung and Tàpies; the Non-Lieux are the most liberated.

Dubuffet’s extraordinary contribution to art history and theory is not only vast and varied, but fundamental to the way artists have approached art practice since. The works in this exhibition attest to Dubuffet’s relevance beyond his own time, not only for his ideas, but for the way his works remain contemporary in their design.

In his lifetime, Dubuffet was the subject of twelve major museum retrospectives including The Museum of Modern Art (1962), which traveled to The Art Institute of Chicago and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Tate, London (1966); Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam (1966); Museum of Fine Arts, Dallas (1966), which travelled to the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Montreal (1969-70); and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1973, 1981). Dubuffet’s work can be found in more than fifty public collections worldwide.

-

Jean DubuffetPiano1966Vinyl on canvas50 3/4 x 37 5/8 in

Jean DubuffetPiano1966Vinyl on canvas50 3/4 x 37 5/8 in

128.8 x 95.5 cm -

Jean DubuffetMire G72 (Boléro)1983Acrylic on paper, mounted on canvas26 3/8 x 39 3/8 in.

Jean DubuffetMire G72 (Boléro)1983Acrylic on paper, mounted on canvas26 3/8 x 39 3/8 in.

67 x 100 cm -

Jean DubuffetAmoncellement à la Corne1968Vinyl paint on epoxy resin22 x 23 1/2 x 18 3/4 in

Jean DubuffetAmoncellement à la Corne1968Vinyl paint on epoxy resin22 x 23 1/2 x 18 3/4 in

55.8 x 59.6 x 47.7 cm -

Jean DubuffetSite avec 5 personnages (E 175) 13 juin 19811981Acrylic on paper, mounted on canvas19 1/2 x 26 3/4 in

Jean DubuffetSite avec 5 personnages (E 175) 13 juin 19811981Acrylic on paper, mounted on canvas19 1/2 x 26 3/4 in

49.5 x 67.8 cm -

Jean DubuffetInspection du territoire (F 141) 1 er septembre 19821982Acrylic on paper, mounted on canvas26 ⅜ x 39 ⅜ in. (67 x 100 cm)

Jean DubuffetInspection du territoire (F 141) 1 er septembre 19821982Acrylic on paper, mounted on canvas26 ⅜ x 39 ⅜ in. (67 x 100 cm)