Jorge Eielson

Timothy Taylor is honored to present an exhibition of works by Peruvian artist Jorge Eielson at the gallery’s New York location. Organized in close collaboration with the Archivio Jorge Eielson, the exhibition focuses on the artist’s Quipus, a series of knotted, twisted, and stretched canvases that extend into three dimensions. This is the first show of Eielson’s work in New York since his 2016 solo exhibition at Andrea Rosen Gallery. A Quipu by Eielson is currently featured in the exhibition Artist’s Choice: The Shape of Shape, curated by artist Amy Sillman at the newly reopened Museum of Modern Art, New York.

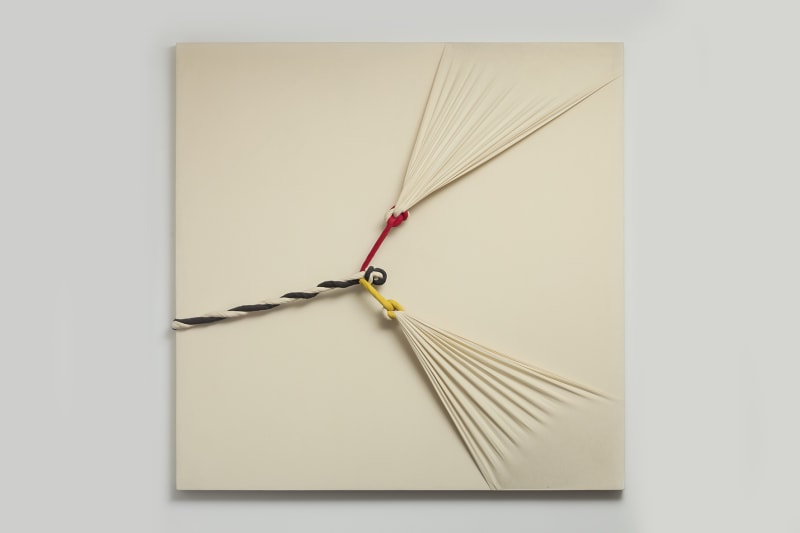

A poet and a visual artist, Eielson is best known for his Quipus series, an exploration of material, form, and communication that he began in 1963 and continued for four decades. The works are conceptual reinterpretations of ancient quipus—a record-keeping system devised by the pre-Columbian Incas of Peru, translated as “talking knots”—and use shape and color to convey meaning. Eielson created his contemporary versions of the ancient device in raw canvas that he stretched, twisted, knotted, and then painted in monochrome or polychrome bands, with each hue, knot, and intersection representing a symbol or word. The torsion and tension of the fabric break out of the two-dimensional boundaries of the flat surface, providing space for additional meanings in Eielson’s singular visual and linguistic system.

Eielson presented his first quipus at the 1964 Venice Biennale, one of four Biennales that he would participate in in his lifetime. They caught the attention of Alfred Barr, founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, and collector Nelson Rockefeller, each of whom purchased them for their collections. Timothy Taylor’s exhibition includes examples from 1966 to 1992, as well as works from Eeilson’s related Nodos series, small sculptures made from knotted fabric.

The Quipus and Nodos embody Eielson’s position as both a distinctly Peruvian artist and an engaged member of the international avant garde. He rose to prominence as part of the Peruvian movement known as “Generation 1950,” before relocating to Europe, first traveling to Paris in 1948 and then to Italy in the 1950s. In Europe, Eielson came in contact with artists including Lucio Fontana, Salvatore Scarpitta, Cy Twombly, Mimmo Rotella, and Alberto Burri — encounters that provided crucial stimuli for the development of his highly personal visual language, which further evolved with his move to Rome in 1970. At the same time, his work remained tied to his birthplace:

The quipus define the two opposite shores of his work: on the one hand, his native culture of Peru; on the other, the world and the universe within a cosmic context. His artistic language is a universal and international one . . . It was the knot— understood as a sign, both ancestral and linguistic, of the tension between matter and the longing for space—that was the heart of his creative process.

Simultaneously, Eielson’s work is regarded as a precursor to conceptual art. The French critic and theorist Pierre Restany explains the novelty of his knot with respect to the contemporary international milieu of experimentation: “Eielson’s gesture is different from the appropriating one of the nouveaux réalistes or the manipulative one of arte povera…his gesture is an existential act taken to paroxysm by the physical tension and the concentration of energy. When the artist’s energy is used up, it is because it has been fully transferred to the quipus. The deepest analogy, as Eielson loves to say, is offered by the gesture of Fontana’s infinitely related ‘slashes.’”