The Tightrope Walker

Anna-Eva Bergman, Bernard Buffet, Jean Dubuffet, Hans Hartung, Georges Jouve, Mathieu Matégot, Serge Mouille, Alexandre Noll, Charlotte Perriand, Jean Prouvé, Germaine Richier.

Borrowing its title from an essay by Jean Genet, The Tightrope Walker will explore the interface between fine art practice, design and furniture within the radical framework of Paris in the aftermath of Nazi occupation and the Second World War.

This exhibition represents a very rare meeting of art and design in a gallery context. It will explore how artists and designers sought simplicity and honesty amidst a growing appreciation of the ordinary and the everyday during this key transitional period in European history.

From 1945, artists and designers needed a way to renew art and culture having emerged into a blasted and impoverished landscape, haunted by horrific imagery of death and destruction on an unimaginable scale. Post-occupation Paris was Europe’s primary artistic and intellectual hub, packed with a rich mix of artists, designers, philosophers and poets. Artists and designers wanted to work both with and beyond the scarring effects of the recent past – they valued utility and practicality and celebrated the mundane and the everyday. Developing new forms of realism, they created interior and private worlds, and found inspiration in uncontaminated natural and primitive forms.

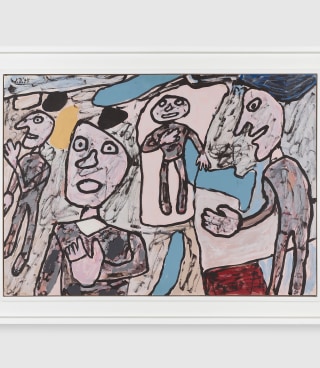

Jean Dubuffet’s appreciation of l’Art Brut, the work of children and untrained artists, led him to create works that celebrated the poetry of ordinary life. His naked male and female figures are rendered with humour and tenderness – the ‘pisseurs’ or ‘corps de dames’ radiate earthy humanity and energy. Rejecting the elegance of oil as a medium, from 1946, Dubuffet added dust, string, gravel and sand to his paints and created a rough plaster-like surface into which the image had to be cut or etched in a graffiti style.

After the war, like Dubuffet, sculptor Germaine Richier sought refuge from the deadening influence of tradition and civilised culture, and found inspiration in ancient folklore and native traditions, drawn from memories of her childhood in Provence. Despite this, Richier’s solitary and anguished bronze figures are heavily scarred and pitted, evoking decay and anxiety; they simultaneously testify to man’s indomitable spirit as well as the fragility of the human form.

Hans Hartung, the German-born émigré who made France his home, and lost a leg fighting with De Gaulle’s forces, developed a form of abstract painting that was to be the image of the artist’s inner self: a psychograph in paint. These paintings, which represent specific existential moments, are often composed of dramatic sheaves of dark brush strokes set against a light washed background.

The Norwegian artist Anna-Eva Bergman settled in Paris in the early 1950s. Originally an illustrator from Norway, in Paris she developed her mature style – moving away from the influence of line and surrealism she developed paintings and gouaches with strong, bold, biomorphic and totemic forms.

Udo Kittelmann writes ‘anyone today, in the 21st century, wanting to find out how Europe felt in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, and what visual idioms were symptomatic of the day, must turn to Bernard Buffet’. Buffet, the French painter known for his ‘miserabilist’ black out-lined figurative paintings, was the most successful and in demand painter of his day. Yet he paid a heavy price for his meteoric rise: tarnished by his lavish lifestyle, critics, art historians and museums ignored his place in post-war art history. Now his work is being re-examined by a new generation of curators and critics, who appreciate its honesty, its ‘incongruous richness’, and its pre-figurement of consumer culture and pop art.

In 1957, Steph Simon opened a gallery to showcase the modernist designer architects Jean Prouvé and Charlotte Perriand, the lighting designer Serge Mouille, and the ceramicist Georges Jouve. The works made by these designers perfectly balanced utility and beauty, very much in line with the combination of radical aesthetics and practical constraints symptomatic of the period known as The Great Reconstruction (1945 – 1960). The work of these designers represents an important shift away from the grandeur, luxury, and embellishments of Art Deco. Using tubular steel and plywood, unusual in domestic furniture, these industrial techniques and materials created a new language for furniture design, one that championed a new modern way of living. Prouvé‘s Chaise Standard remains an emblem of this post-war utilitarian but utopian domesticity.